On a few special Saturdays out of the year, visitors to the St. Louis Science Center are treated with a mind-blowing event: The Amazing Brain Carnival. Featuring a variety of activities for guests to explore how signals are sent through the body and see these cells up close, including a display of a real human brain, the volunteers for the St. Louis Neuroscience Outreach group (STLNO) bring the science of the brain to the public.

“We try to find really fun ways to engage people that doesn’t feel like a lecture. It feels like they’re just having fun, and then along the way, they’re also learning about science,” said Grace Moore, a neuroscience graduate student at Washington University in St. Louis and the STLNO student coordinator.

STLNO and their Amazing Brain Carnival are just one of several examples of science outreach programs undertaken by academic scientists with the goal of bringing research or general science topics to the public. Although public trust in scientists remains high in the US and abroad, one US survey showed that respondents were concerned that researchers did not share their values.1,2

By engaging with their community, scientists can improve these relationships and trust in research.3,4 However, these programs are not one-way streets. Participating in science outreach also helps researchers become better scientists.

Short Science Interactions Leave Lasting Impressions

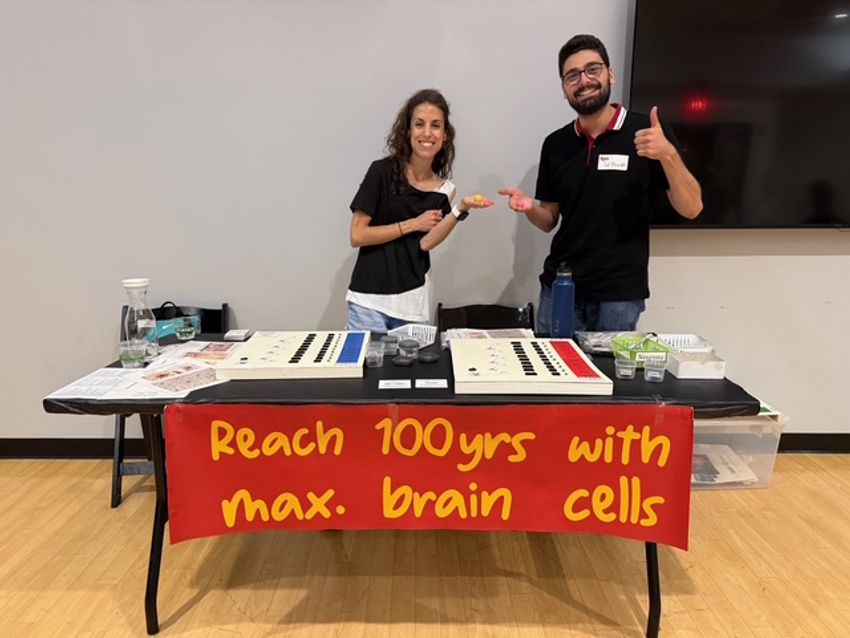

STLNO started as a program funded by the National Science Foundation to improve graduate students’ abilities to communicate their science. As a secondary goal, the group aims to bring the current state of neuroscience to as many people from as many backgrounds as possible. According to Erik Herzog, a neuroscientist at Washington University in St. Louis and the faculty mentor for STLNO, the Amazing Brain Carnival connects between 4,000 and 8,000 people a year with neuroscience activities.

Volunteers for STLNO teach museum guests about the brain, giving them an opportunity to learn how the organ works and interact with scientists.

Grace Moore

While these events may reach many people, one challenge science outreach organizers face is determining the impact of their programs. For the Amazing Brain Carnival, STLNO volunteers survey their guests about their understanding of science concepts and the brain after attending the event, and they consistently see positive outcomes. According to Herzog, a qualitative—but just as important—measure of success is feedback from elementary and middle-school students, who wrote in letters that they want to go into science after visiting STLNO’s event.

Other science outreach groups, like the Graduate Student and Postdoctoral chapter of the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos, Hispanics and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS) at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis) are focused on promoting underrepresented minorities in STEM. The SACNAS team sees outreach as an important way to improve representation in STEM. “I’m Mexican American, I did not see anyone in science growing up; TV, professors, high school teachers—just no representation,” said Laura Kojima Todd, a reptile amphibian biologist at UC Davis who leads the K-8 outreach events with the chapter.

SACNAS coordinators and volunteers undertake science outreach events to engage students of all age groups. To reach underrepresented and minority students in STEM, the group focuses on schools that receive Title I funding which goes to schools with lower socioeconomic status.

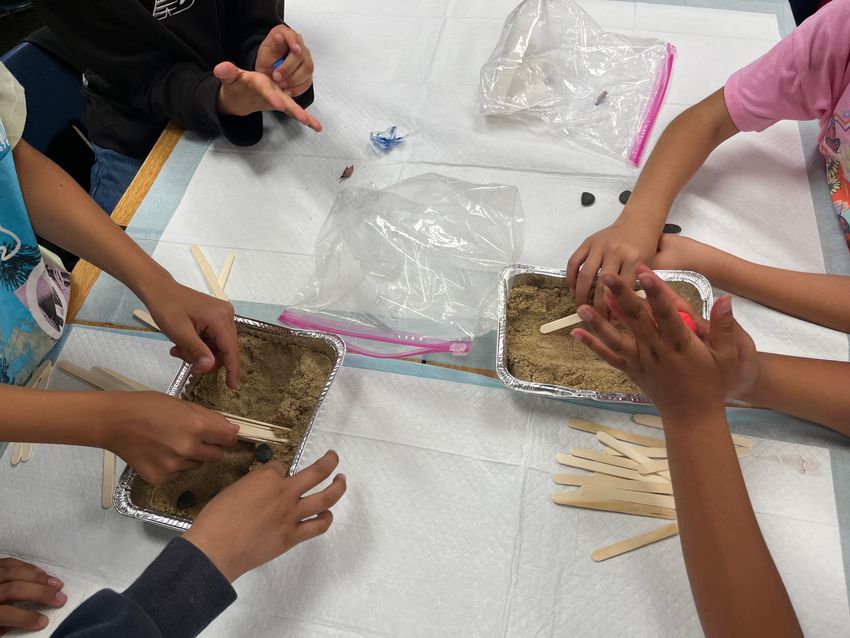

Kojima Todd said that she and other outreach coordinators reference the schools’ curriculums to come up with topics and presentations to bring to students. Recently, they have done activities on wildlife and keystone species in an area.“[It] was pretty neat for me to get my feet wet with the lesson plan and come up with kind of how do I incorporate not just a bunch of PowerPoint slides for them to look at, but like a more hands on experience for them to actually learn their different local wildlife and animals,” said Kojima Todd.

Students built models of beaver dams as part of a science outreach activity learning about these animals.

Laura Kojima Todd

In the classroom, Kojima Todd said that it can be hard to measure these kinds of impacts, but that she gauges the students’ interest by their participation. Although many students are quiet at the start of her presentations, “by the end of the class, they’re just calling you left and right,” she said. “You can just tell that there’s this little bit of curiosity that’s been starting to grow in their head.”

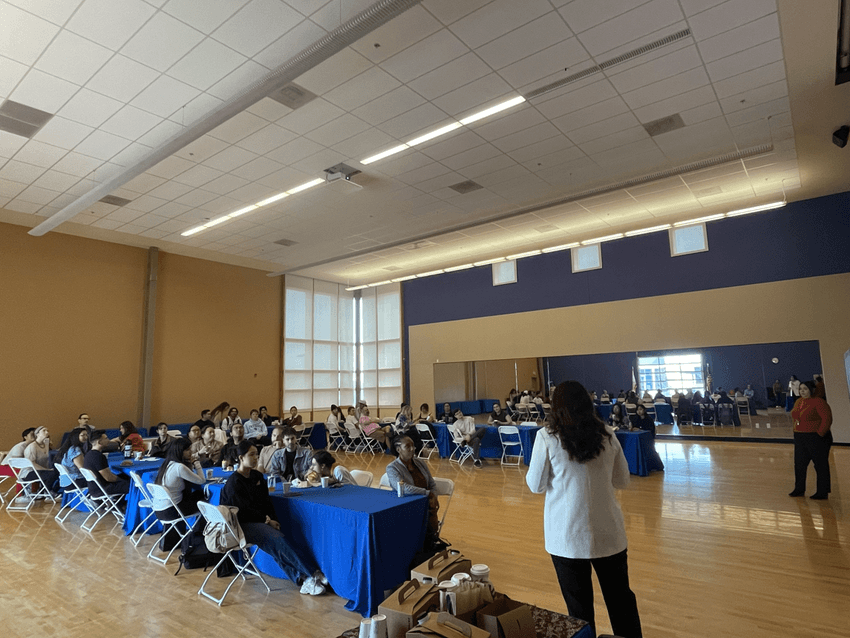

To reach older students, SACNAS volunteers visit local community colleges, which many underrepresented students attend because of their affordability. One event, Café con Pan Dulce, included more than 50 students interested in learning about graduate school. As a community college alumna, the event coordinator, ecologist Karen Gallardo Cruz, said, “There’s very limited understanding of what careers are available to people in science.” She added, “They’re seeing a different version of what a scientist is. And that’s something that I would have liked to see when I was in their position.”

Indeed, these types of short duration outreach activities have been shown to improve students’ interest and understanding of science.5 Additionally, connecting students from minority backgrounds with scientists have been shown to improve both trust and interest in science in people from underrepresented backgrounds.6

Community and Long-Term Impact Through Science Outreach

While one-time or infrequent interactions with scientists through outreach activities can provide valuable experiences, regular, repeated events provide more chances to make lasting impressions on students.7,8

Beyond the Amazing Brain Carnival, STLNO also hosts a trivia competition and mentoring program. “We really believe that you can be inspired and confident in moving forward as a scientist by just meeting people who are a little bit a little ahead of you,” Herzog said.

“Practicing communicating about science at different levels makes you a better scientist.”

—Grace moore, Washington university at st. louis

In the case of their trivia competition, the Brain Bee, university undergraduates and former Brain Bee winners tutor high school students in neuroscience. Meanwhile, another activity, Brain Discovery, brings graduate students and researchers into classrooms once a week for six weeks. “It’s really beneficial for us to have those repeated interactions of going into the same classroom, visiting the same students for six weeks in a row,” Moore said.

Herzog recalls seeing students return for STLNO’s Brain Bee throughout high school and eventually go through college to major in neuroscience. “It’s been really fun for me as a professor to realize I’ve known this student since high school, and they’re now training to be a neurosurgeon,” he said.

SACNAS also partners with community colleges to provide professional development workshops for students participating in a summer research program. “Giving these students the opportunity to not only have access to people that they can talk to as mentors, but also experience research firsthand, is super valuable, because now they can see, okay, research is actually a path that I’m interested, that I want to pursue, or research is not for me,” said Gallardo Cruz.

Jasmine Esparza, a molecular biologist and cofounder of the Graduate Student and Postdoctoral chapter of SACNAS at UC Davis, said that they have seen community college students who attended a SACNAS outreach event and then participated in summer undergraduate research. “Now we’re seeing them here next to us at the same university. For me, that’s success,” she said.

She added, though, that even if the students don’t choose to pursue science, outreach activities “[are] still creating, a generation that is able to ask questions [and] is able to be excited about different topics at school.” She added that instilling this curiosity and problem-solving skills can help the students address problems later on. “For me, that is what excites me the most about outreach, being able to plant seeds to make change in the future,” Esparza said.

Indeed, science outreach may have value even when a learned skill can’t be measured. “Every learning experience can be a factor positive or negative, and it can reinforce something that you’ve learned at school that you’d like to learn more about. It can expose you to something new. It can give you a glimpse of a lifestyle or a career path that seems intriguing,” said Sandra Laursen, an education researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder. “There’s reason to think we should keep doing it, even if we can’t measure in detail the specific impact of our thing.”

For example, these interactions allow Herzog, Moore, and other researchers the chance to tell people about what they do face-to-face. “It’s been really important to see that we have a real an opportunity to have a real dialogue with people about why we do what we do and how we think it can impact people,” Herzog said. Moore agreed. “It’s becoming increasingly important for anyone involved in science to really think about how science is perceived by the public,” she said.

Graduate students from UC, Davis visited undergraduates at a local community college to answer questions about graduate school over Mexican sweet bread and coffee.

Karen Gallardo Cruz

Herzog added that, as a result of being in a public capacity, policy makers contact STLNO to learn about the value of basic research. “This is a chance for us to start to be really clear about how what we do is leading to new inventions, new companies, new therapies and new technologies,” Herzog said.

In addition to being a resource for proposed policy changes, Herzog said STLNO also provides support to the community after storms. “We are now trusted colleagues in the mission that the city has.”

Gallardo Cruz said that working with students inspires her and reminds her of why she is doing what she is doing. “Not only do I want to do research that’s useful and interesting, but also I know that I’m a role model,” she said, adding, “It gives a little more spice to this life of a PhD student where we’re just constantly working, constantly grinding, and maybe constantly being pressured also to produce, and it feels nice to contribute something as well to the community.”

Science Outreach Supports Scientist Training

Even though most researchers agree that science communication and outreach efforts are important, many scientists don’t want to participate in these efforts.9,10 In surveys, researchers indicated that their institutions do not adequately support science outreach activities, and many researchers don’t think that scientists in general are good communicators.9,11 Additionally, having peers who don’t view doing outreach as valuable scientific contributions discourages some scientists from getting involved.5,11,12 Researchers also worry about how taking time away from the bench will impact their education or career success.11-13

Despite this, beyond benefits to their community, Laursen said, “The impacts [of science outreach] can be more profound on the scientists who do the work.” For example, most researchers who participate in science outreach report improved communication skills.5,14 “Practicing communicating about science at different levels makes you a better scientist,” Moore said, adding that outreach activities force researchers to think about how to explain a complex topic with people who don’t have the same knowledge.

Regarding their academic performance, involvement with outreach activities does not significantly detract from researchers’ scientific publications or professional engagements.13-15 In fact, Esparza and Gallardo Cruz agreed that participating in outreach can provide many transferable skills like project management, grant writing, and mentoring skills and demonstrates commitment to service, all of which are important for academic positions.

“My graduate training has been enhanced by my interactions with the public and seeing what do people think of the scientific landscape right now? What do they think we’re actually doing? Do they think this is a viable career for their children? Do they think this is worth their taxpayer dollars? And I think it just really puts into perspective what I’m doing and what is worth doing,” Moore said.

- Cologna V, et al. Trust in scientists and their role in society across 68 countries. Nat Hum Behav. 2025;9:713-730.

- Lupia A, et al. Trends in US public confidence in science and opportunities for progress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2024;121(11): e2319488121

- Woitowich NC, et al. Assessing motivations and barriers to science outreach within academic science research settings: A mixed-methods survey. Front Commun. 2022;7:907762.

- Millar V, et al. University run science outreach programs as a community of practice and site for identity development. Int J Sci Educ. 2019;41(18):2579-2601.

- Laursen S, et al. What good is a scientist in the classroom? Participant outcomes and program design features for a short-duration science outreach intervention in K–12 classrooms. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2007;6(1):1-83.

- Golle J, et al. How science outreach with children can promote equity and diversity. Trends Cell Biol. 2022;32(8):641-645.

- Miranda RJ, Hermann RS. A critical analysis of faculty-developed urban K-12 science outreach programs. Penn GSE Persp Urban Educ. 2010;7(1):109-114.

- Metz CJ, et al. The in’s and out’s of science outreach: assessment of an engaging new program. Adv Physiol Educ. 2018;42(3):487-492.

- Rose KM, et al. Scientists’ incentives and attitudes toward public communication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(3):1274-1276.

- Besley JC, et al. Scientists’ views about communication training. J Res Sci Teach. 2015;52(2):199-220.

- Ecklund EH, et al. How academic biologists and physicists view science outreach. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36240.

- Andrews E, et al. Scientists and public outreach: Participation, motivations, and impediments. J Geosci Educ. 2005;53(3):281-293.

- Doberneck DM. Are we there yet?: Outreach and engagement in the consortium for institutional cooperation promotion and tenure policies. J Community Engagem Scholarsh. 2016;9(1):8-18.

- Clark G, et al. Science educational outreach programs that benefit students and scientists. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(12):e1002368.

- Jensen P, et al. Scientists who engage with society perform better academically. Sci Public Pol. 2008;35(7):527-541.

- Bentley P, Kyvik S. Academic staff and public communication: A survey of popular science publishing across 13 countries. Public Underst Sci. 2010;20(1):48-63.

- Kassab O. Does public outreach impede research performance? Exploring the ‘researcher’s dilemma’ in a sustainability research center. Sci Public Pol. 2019;46(5):710-720.